Transformative Environmental Education (TrEE) is an approach to learning that transforms a child's perceptions and understandings of the environment and community of life. It is place-based, developmentally-sensitive, and honors inner and outer dimensions of human experience. Through genuine connection with Nature, it inspires curiosity, wonder, care, and reverence for the more-than-human world.

TrEE is integral and integrated, nurturing the whole child through learning opportunities that provide immersion and exploration in Nature as well as cultivate creative expression through storytelling, ritual, and the arts. It further engenders a sense of agency and environmental citizenship through meaningful action on behalf of the environment in local parks, refuges, and wildlands.

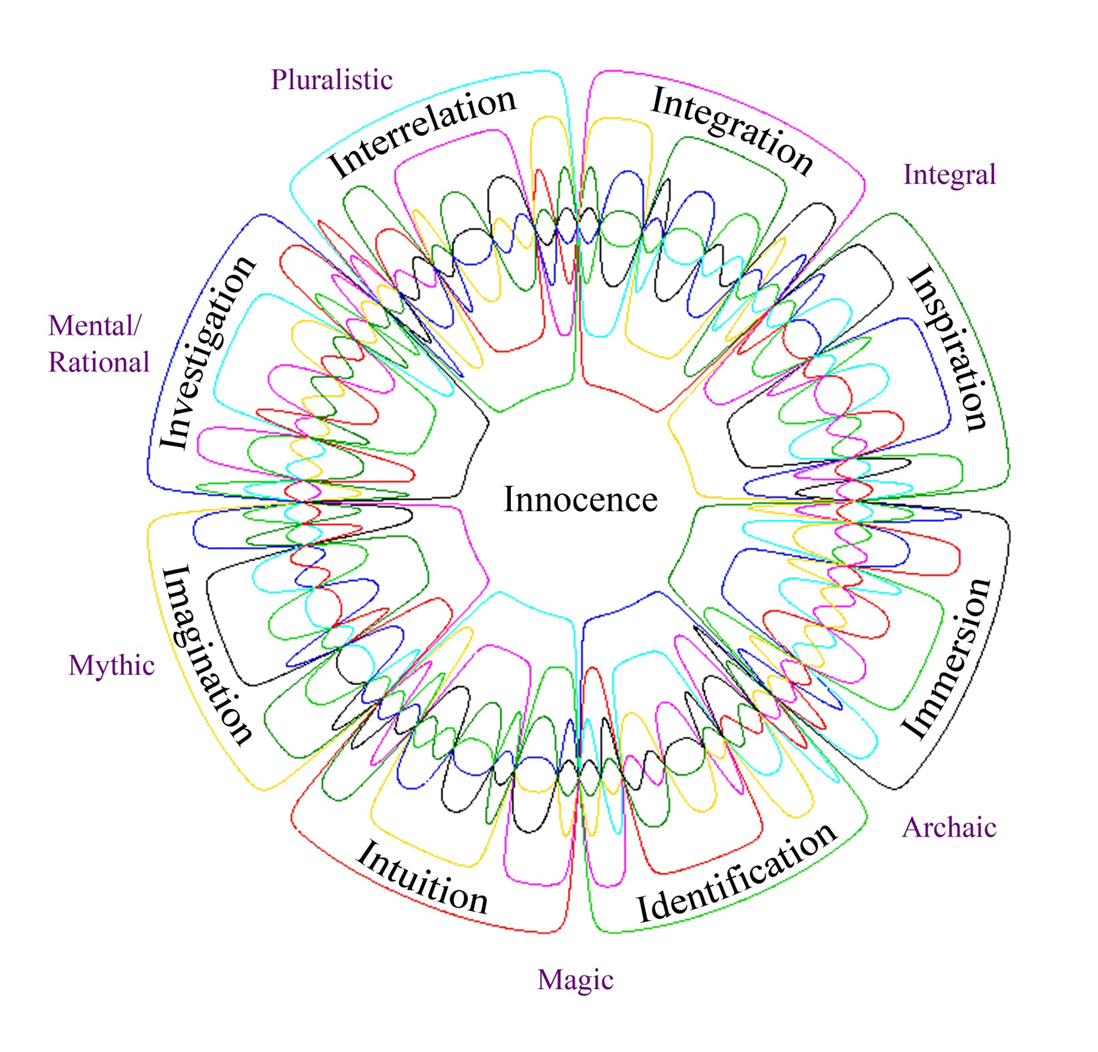

The model for TrEE (Figure 1) helps formal and non-formal educators design learning opportunities that facilitate many ways of knowing during the process of learning and create the possibility of realizing Earth Identity—our physical, relational, and spiritual interconnections with Nature.

Figure 1

Background Venn diagram by Frank Ruskey and Mark Weston, More fun with symmetric Venn diagrams, Theory of Computing Systems, 39 (2006) 413-423.

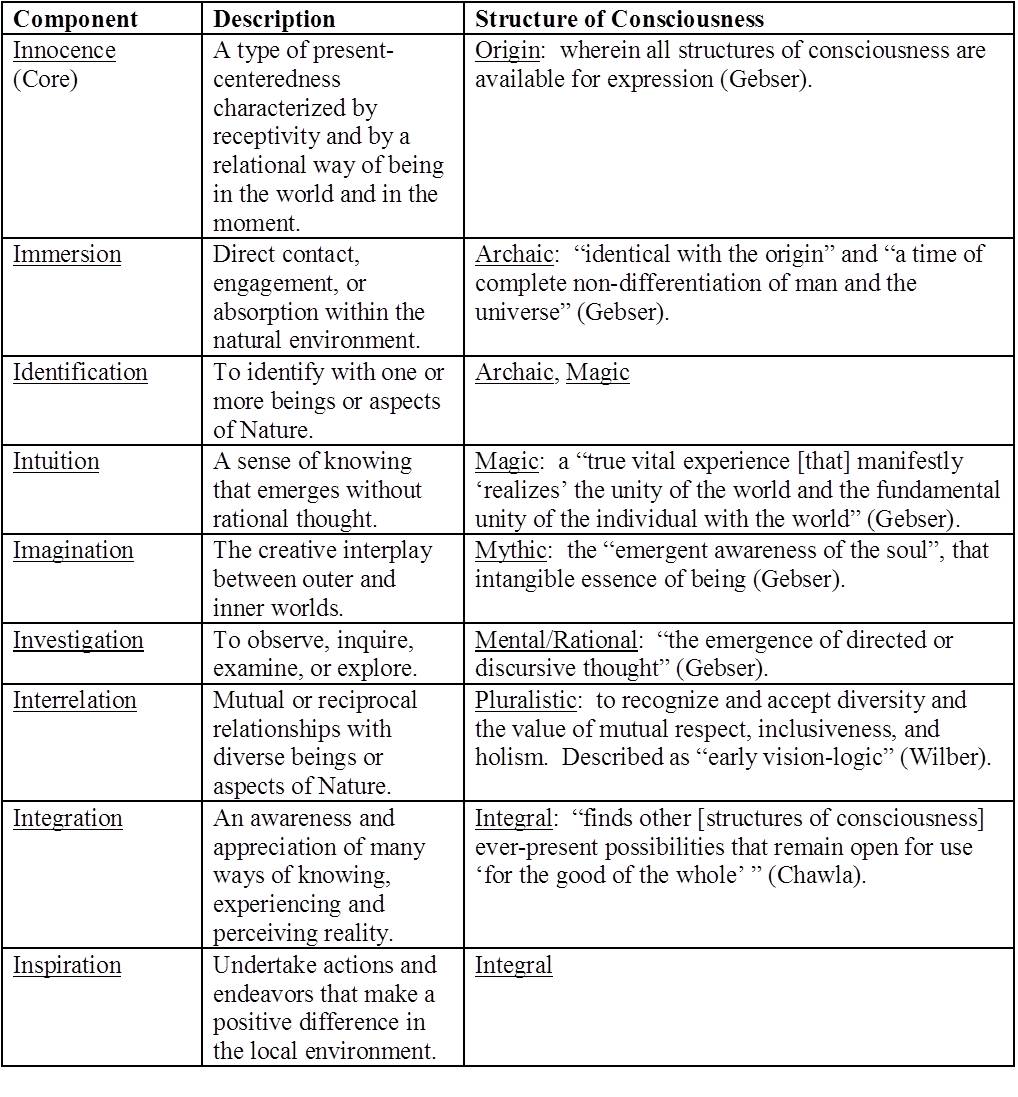

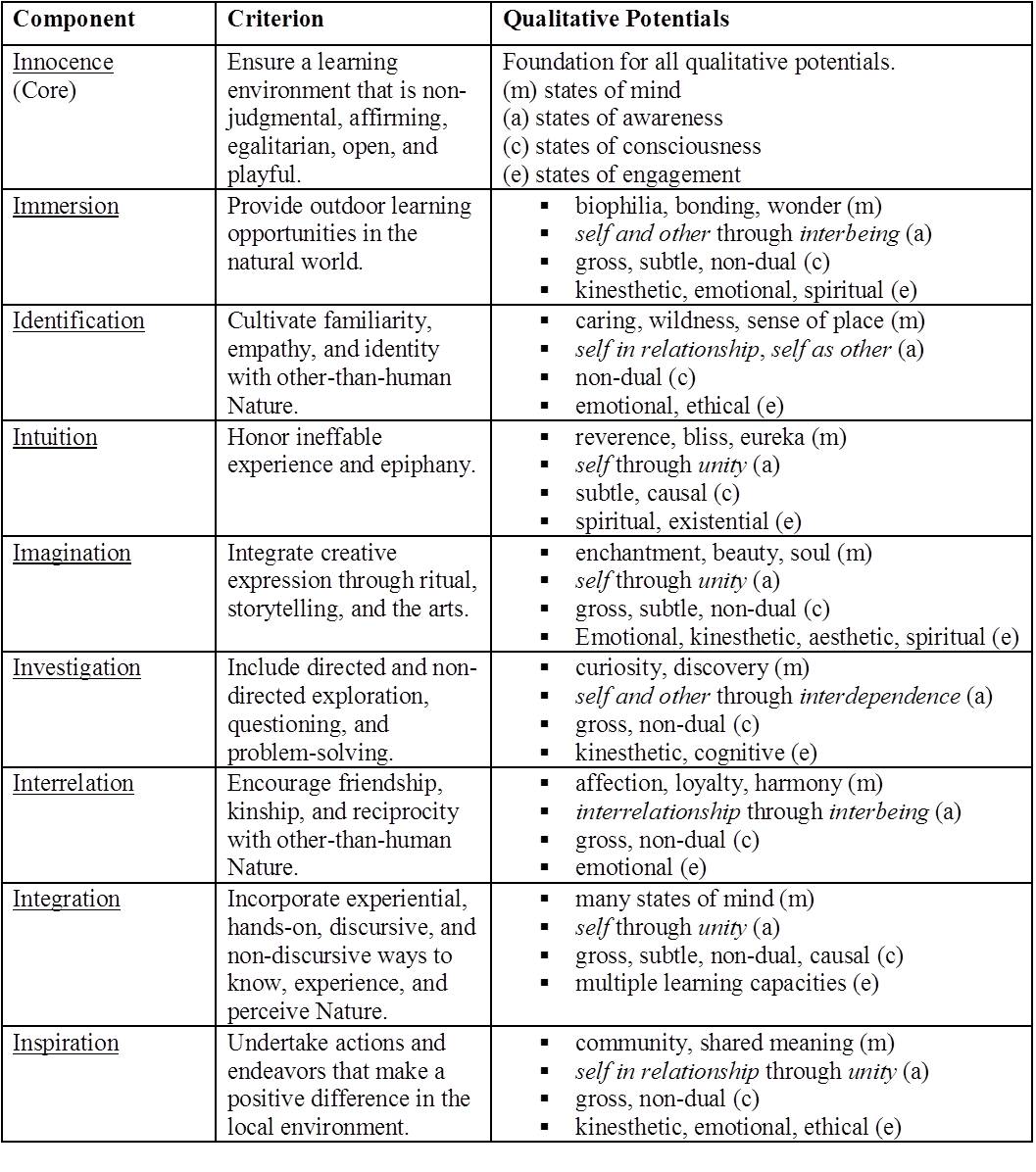

The model is represented by a Venn diagram and defined by six structures of consciousness, eight components, and the core. Structures of consciousness determine how we perceive and experience the world. Each component corresponds with a specific structure of consciousness and represents a way of knowing that may lead to intensified awareness—an experience of concentrated or acute perception—across many states of consciousness and within multiple learning capacities. The core, innocence, is the doorway to a fullness of experience within each component. Table 1 describes each component and the corresponding structure of consciousness.

Table 1

Chawla, Louise. (2002). Spots Of Time: Manifold Ways Of Being In Nature In Childhood. In P. H. Kahn Jr., & S. R. Kellert (Eds.), Children In Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, And Evolutionary Investigations. (pp. 199-225). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Gebser, J. (1985). The Ever-Present Origin. Translation by N. Barstad with A. Mickunas. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala.

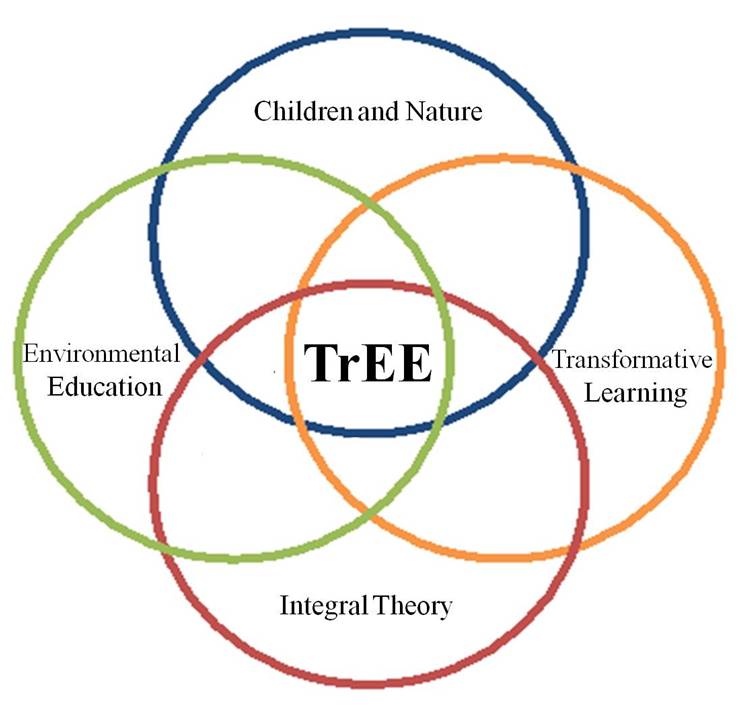

The model is informed by Integral Theory, Environmental Education, Children and Nature, and Transformative Learning (Figure 2). It highlights non-discursive experience, subjective and contextual knowledge, and multiple learning capacities—such as emotional, kinesthetic, aesthetic, ethical, spiritual, and existential capacities.

Figure 2

TrEE challenges conventional approaches to environmental education that primarily emphasize discursive thought, objective and abstract knowledge, and the cognitive learning capacity. It also addresses environmental concerns in ways that are life-affirming, empowering, and hopeful.

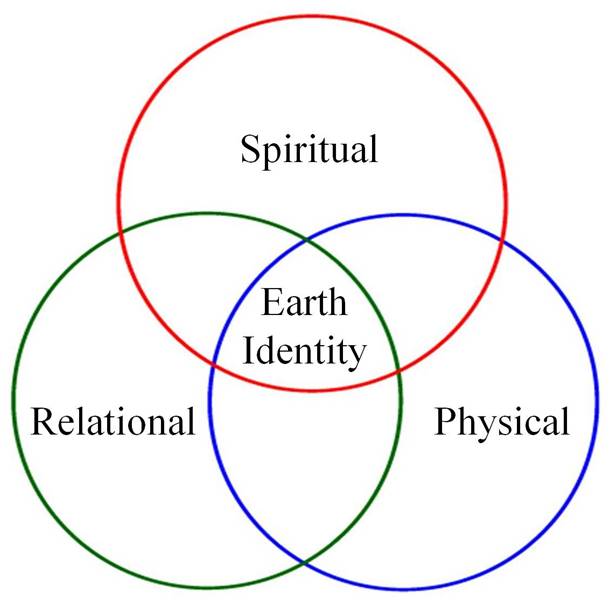

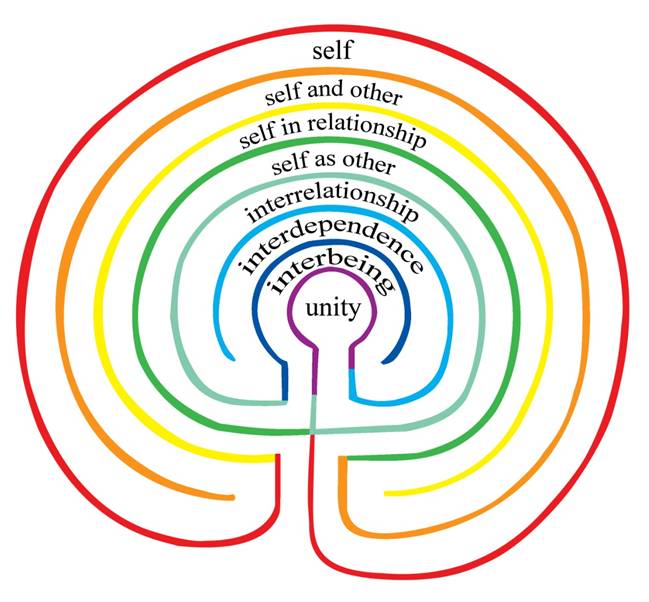

Earth Identity is the sense of self shaped and informed by one's physical, relational, and spiritual interconnections with Nature (Figure 3). It is more encompassing than self-identity (ego) and is defined by one's affiliation and identification with other-than-human Nature. It is essentially ecological, embracing the interdependence, interconnectedness, and unity of all life.

Figure 3

Earth Identity may be realized through many ways of knowing, being, and perceiving. The realization of Earth Identity is a process of unfolding characterized by experiences of intensified awareness. These experiences may lead one to apprehend the fullness of being human—the boundaries of self blurred by the reality of our radical interconnectedness with all of existence.

The realization of Earth Identity inspires a sense of personal meaning. It may also facilitate shared meaning through its embrace of the web of life, giving rise to experiences of community, wholeness, and well-being.

Intensified awareness is an experience of concentrated or acute perception. It occurs when a person perceives an increase in the resolution of reality, analogous to an increase in the pixels of a digital image.

Kinds of Intensified Awareness

- Self is an experience of singularity and separateness.

- Self and other is the recognition of another being or entity.

- Self in relationship is characterized by reaching out to associate with one or more beings or entities.

- Self as other is identifying with one or more beings or entities.

- Interrelationship is an association with one or more beings or entities that is characterized by reciprocity.

- Interdependence is experiencing a network or system of interrelationships.

- Interbeing is a radical interconnectedness with all life.

- Unity is a state of being one with all that is.

In the context of TrEE, there is a spectrum of intensified awareness. Eight kinds of intensified awareness comprise this spectrum. Each kind is qualitatively different, rendering a unique experience or perception of reality. I use the seven-circuit labyrinth as a diagram to illustrate the non-developmental, non-hierarchical nature of the spectrum (Figure 4).

Figure 4

The model for TrEE can be understood as a wheel of criteria (Figure 5) that informs, guides, and helps educators determine the types of activities or experiences needed to create integral and transformative environmental learning opportunities. These criteria are based on components of the model and can be used to augment conventional environmental education; to develop non-formal environmental learning opportunities; and to create school, family, and community-based programs that lead to expressions of sustainability and resilience. These expressions foster a sense of personal and shared meaning.

Figure 5

Meaning is not measured by discursive academic outcomes alone, but arises through non-discursive outcomes, as well. Non-discursive outcomes are qualitative experiences that may influence perception, behavior, and actions. In the context of TrEE, these experiences are qualitative potentials—possible outcomes associated with the components of the model. The list of qualitative potentials in Table 2 is not exhaustive, but indicates outcomes that are representative examples for each component.

Qualitative Potentials

- States of mind are feelings of intense focus, magnitude, or significance and include experiences such as curiosity, wonder, and reverence.

- States of awareness are represented by the spectrum of intensified awareness—experiences of concentrated or acute perception.

- States of consciousness are characterized by different "modes of experience or energetic feeling" (Wilber) and include gross (physical, sensorimotor), subtle (dream-like, imagery), non-dual (flow, oneness), and causal (formless, emptiness) experiences.

- States of engagement are determined by the activation or exercise of a given learning capacity—the potential to learn and understand—and include examples such as emotional, kinesthetic, and spiritual capacities.

Wilber, K. (2007). The Integral Vision: A Very Short Introduction to the Revolutionary Integral Approach to Life, God, the Universe, and Everything. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambala.

Table 2

TrEE offers an alternative to conventional environmental education and is holistic and integral, valuing the soul of each child more than artificial standards and norms. It honors children in their wholeness and provides opportunities for them to experience the fullness of being human and to realize Earth Identity.

Photo Credit: banner photo, Cheryl Cannon